The Gospel in a different way

In the XIᵉ century, dissident spiritual movements developed, while the Catholic Church grew in power and structure. Thus, “Cathar” communities developed throughout Western Europe (Flanders, Burgundy, Champagne, England, Italy, Germany) under various names (piphles, publicans, weavers, patarins, bougres, albigeois).

It was in the Occitan region that Catharism experienced its most significant expansion. Throughout the region, men and women, whether simple sympathizers, confirmed believers or openly religious, embraced this alternative conception of Christianity.

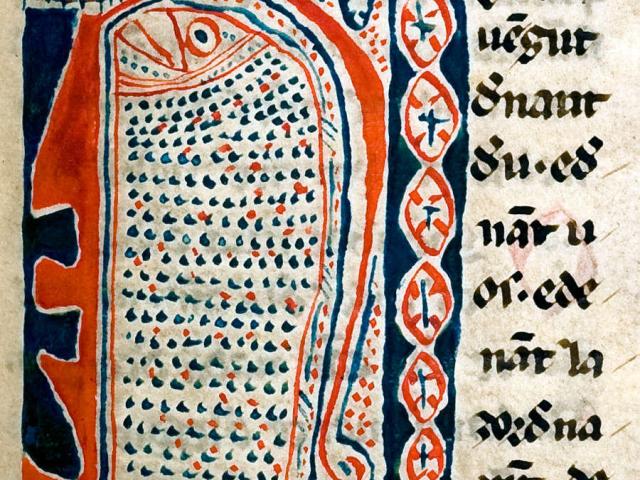

Their worldview is based on a different interpretation of the Gospels. According to these believers, Good and Evil rule heaven and earth respectively. Christ is said to be a pure spirit sent to earth by God to bring people the baptism of the Holy Spirit: consolation. This baptism is given by the bonshommes to believers by the laying on of hands, and only from the age of 13 or 14 onwards, so that the believer commits himself in full knowledge of the facts and by conviction.

prayer-spiritual-hands-sun-sun-sunset

prayer-spiritual-hands-sun-sun-sunset